I had a strange thing happen when visiting the labyrinth (or, labirintus) in Budapest last summer, famously called “Dracula’s chamber.” I'd wanted to visit for years, but never had. Finally, a decade later, I made arrangements to take the children, along with my friend's young son, for an afternoon excursion.

Tickets in hand, steep stairs down, the labyrinth was a welcome escape from the heat. But escapes can be troubling. The walls oozed dampness and smelled of unsettling feelings. As I rubbed my goose-bumped arms, memories of my first days in Budapest rose in my mind. I could feel how my homesickness, like claustrophobia, had tangled with longing and was lodged in my chest, I’d tried to break free in a close-fitting dress and visits around the city. I could still feel the tug of my now-lost silver earrings.

The damp cave air and sudden darkness also surprised the children. Whether or not they were remembering their times past, I’m not sure, but they pressed close to me as we descended. Their fingers clasped around my waist. Admittedly, I wanted to stop to read the plaques about the well-dressed wax figures, and the uses of the labyrinth, but I was unable. I had expanded into a giant mother, my body stretched across four bodies. We were a centipede navigating the subterranean. Spiraling, like a clot, for long minutes.

There was nothing strange about this. I’m accustomed to assuaging situational fright in children. I made them laugh. When we reached one corridor, ominously labeled with something related to Dracula’s imprisonment and burial, the children released me. They’d warmed to the labyrinth and begun to enthusiastically joke around. They peered down a hallway, their backs to me. I was delighted by their delight and lifted my phone camera to photograph their silhouettes, framed by the warmth of an imitation oil lamp.

And isn’t this strange. That’s when I saw a young woman. This is very clear to me. I felt her presence. I saw her face. She was in front of me. Her eyes locked mine. She was not me. This was no selfie. She was, well, young. Very young. And imploring, but also curious. She was no one I knew. She wanted to be near me, like a child.

At this point, the children had rounded the bend. There was no one around but me and this young woman.

I wanted to open the camera. I wanted to press the shutter—my impulse to document is very practiced in this age of smartphones. But other people approached. She vanished. My camera was pointing at a wall. The children were calling from a threshold.

“Mommy, take our picture!”

**

I could have decided I’d slipped into a daydream. That the dampness and descendance from the surface of the day had impaired my cognition.

But I did not believe in this logic.

A young woman had been there, with me. She was invisible but present. Isn’t that strange?

Eventually, I took another picture of the children. We wound our way to the top. At the ticket kiosk, I tucked a free brochure into my purse. And we returned to the blinding glare of the present.

I read the brochure on the train to Vienna, a few days later.

Two hundred and fifty years ago, a young woman had disappeared in the labyrinth under suspicious circumstances. She was somehow related to an impoverished count. A niece? A betrothed? He had been making nefarious deals in the labyrinth with a group of thieves. A debt was unpaid. She was special to him. In an unrecorded effort to recover something that was not freely given, she went missing. Presumed dead. Murdered.

It is reported, the brochure states, that she haunts the labyrinth.

What to read

Christine Smallwood on A Woman In Me by Britney Spears, Britney was trapped in a restrictive conservatorship. Now she’s written a memoir, with a ghostwriter. She’s also active on Instagram. How to make sense of the Britneys we can and can’t see? Smallwood explains.

Alexa, Tell Me About Your Mother (2020) by Jessa Lingel and Kate Crawford for Catalyst. I revisited this essay on why the ghost of the secretary desk endures in AI robots. Lingel and Crawford explain in this accessible peer-reviewed article. A ghost story for our time.

Are you in a portal? by Stubstacker Anne Helen Peterson. Her relatable essay this week makes the internet feel small, but maybe that’s just the power of links. Peterson references writers I read, Claire Zulkey’s irreverent Evil Witches and Amanda Montei’s Mad Woman. She also happens to reside on the island where my grandparents are buried. Isn’t that strange?

Book recommendation

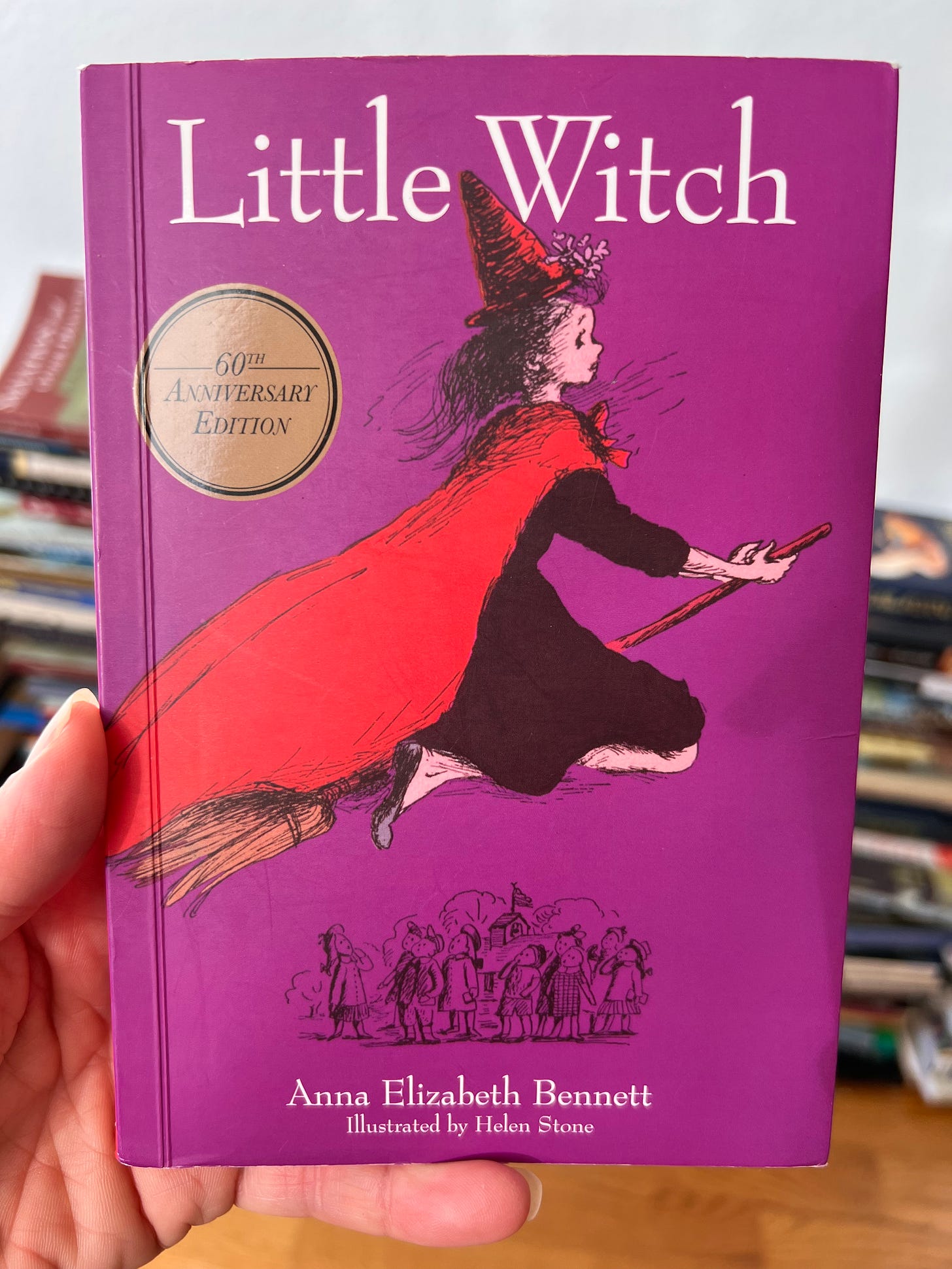

Little Witch

Anna Elizabeth Bennett

I read Little Witch aloud to my daughter. The book deserves a lovely review because it’s strange and it’s nice to have strong feelings of strangeness, but not feel afraid. That’s what I think, at least. There’s so much to daytime that blinds us to all that we cannot see.

I’d be remiss not to end this edition by saying, happy Halloween!

Thank you for reading The Gift,

Monika

The Gift