I’d already been trying to avoid other people’s anxiety about the upcoming presidential election in the United States. Peak election anxiety? It’s only July.

Then, breaking news. A shooting—assassination attempt. I thought grimly, as you probably did too, how awful and not surprising. We live in a country where mass shootings happen in schools. Where I’m worried this horror will be twisted into partisan finger-pointing. Life doesn’t have to be like this. But the next horror seems just around the corner. And that’s the generalized anxiety of the dog days of summer.

What should we do?

In my last issue, I mentioned an old technique I’ve used to answer questions. Book divining, or, bibliomancy. This is the reading of sacred books for divination, or, to gain a sense of possibility. The I Ching, Bible, and sacred Hebrew texts, among others, have historically been used.

A few days ago, inspired by another anxious conversation, I decided to get answers by using a book I had nearby, 5 Simple Practices for a Lifetime of Joy by Amaya Pryce[1], which I picked up at a Little Library in Ballard. Pryce has surmised a range of spiritual and self-help texts into a handy primer. I happened to have it near my desk.

My bibliomancy process is simple

Ask the question aloud

Close your eyes and take a few deep breaths

Slowly open your eyes, open the book

See where your finger is on the page

Q: Should you be worried about the American political climate? About AI?

A: “If it’s something that really grabs your attention, that has a lot of “juice” for you, there’s a reason for that. Carl Jung, the king of the shadow realm, wrote, ‘everything that irritates us about others can lead us to an understanding about ourselves.’ He also said, “To become acquainted with oneself is a terrible shock.” — pg. 109

Pryce gives an example: the know-it-all political ranter who abuses people who agree with the other party, calling them intolerant. How apropos.

Her suggestions on how to identify and heal from the shock of your dark self? Acknowledge, extend compassion. “The whole point of Shadow work is to become whole again by accepting and loving even the parts of ourselves that we’ve previously considered unlovable.”[2]

It’s possible book divining is off-putting to you. Even though the technique is akin to the hermeneutical tradition that informs media and literary studies, suspicions about book divining as something more than a parlor trick, something that can result in credible insight, make sense to me.

Divination requires a strange stretching of the rational mind. One might retort, I know better. Divining is not possible, I can critically think. I am no fool who believes an implausible scenario.

But what if, instead, I’d written that I’d “done my own research” (DYOR), or, used generative AI to answer that question? Just to see.

That seems to be a parlor trick used today to get answers. On this topic, I’ve been thinking about how mediated methods of ascertaining credibility and reliability relate to our contemporary anxieties.

Around the time that I began writing this, Erzsébet Barát, a feminist media studies scholar, a professor at the University of Szeged and Central European University, and—lucky for me—reader of this newsletter, shared an astute essay by linguist Johanna Laakso about what happens when journalists and policymakers use the ease of search, and generative AI, to get definitive definitions.[3] Rather than accepting that the meanings and histories of words are ambiguous and context-dependent, or considering that reading is a task in interpretation, she identifies a trend in people relying on the incomprehensible power of search engines and generative AI, as if it presents reality as it really is.

Accepting the results of AI as reality presents a problem, because, it’s a mediation. And a mediation rooted in control. As the theologian and computer scientist Noreen Herzfeld has pointed out, “computing [is] a military technology designed for surveillance.” [4]

Meanwhile, the trend to “do your own research” (DYOR) or use generative AI for reality typifies belief in the trustworthiness of computational processes to give us answers.

Here’s the zinger. To “know better” by doing my own research using search engines or AI is a consequence of what social theorist Max Weber diagnosed as the disenchantment of Western epistemological structures of power.

With the advent of reason, bureaucracy, and scientific thinking, along with capitalism as a world system, we understand ourselves through dualism. Spirituality, mystery, and the supernatural are implausible.

But spiritual impulses have not disappeared. They’ve become repressed. According to Hannah Arendt in her work on totalitarianism, the repression is a kind of rootlessness: a “situation of spiritual and social homelessness”[5], a lonely place of unrest which leads to a susceptibility for authoritarianism and propaganda.

This is the parlor trick of AI, we believe that the manifestation of surveillance capitalism can be benevolent extensions of our rational minds. But when we look to AI to deliver reality, we risk becoming less human.

—

In the past few years that I’ve used divining as a method of inquiry, I’ve generally found the answers insightful. I get something I need. I can say the same thing for how I use search. I don’t get specific or clear answers, rather, I use the process as a point of departure.

For example, with the Q&A above, I want to dig deeper into taking a look at what irritates me. While I may have brought up politics in the hook of this essay, I have mostly talked about AI writers. I can get uncomfortable when people appear to suggest that writing is a dying profession. That generative AI can enhance creativity and optimize processes.

In this way, I understand, and support, the class action lawsuits of writers and artists suing companies using the vocabulary of copyright infringement and theft. Their human art was stolen to train machines that enrich their developers, entrench surveillance, and outsource imagination and moral decision-making. It’s normal to want to escape.

Let me follow the advice procured from bibliomancy and turn inward: Is anger, and similarly, the impulse to escape, an outgrowth of a repressed fear of AI writers, and the masterminds behind the adoption of this software? Do I belittle others? I have, on occasion, belittled my writer-self, talking myself out of creating.

The concept of the Jungian shadow realm, and the repressed, is helpful for understanding acts of violence. A harm must be faced compassionately, non-violently, to heal. Because the injury is also within you. Don’t hurt yourself.

A final word on fools. According to Rachel Pollack, in Tarot, The Fool is the beginning, and like an egg, a paradox.[7] The fool is the ambiguous figure who is about to take a journey through life’s mysteries, or, the Major Arcana, and what’s possible? As a cosmology, Tarot represents a cycle of living, not linearity, with an ending in heaven or hell. In these days of violence, wouldn’t you like to be the fool who believes in an implausible scenario? That we can be enchanted? Can we learn to read again in our age of smart machines?

In other news

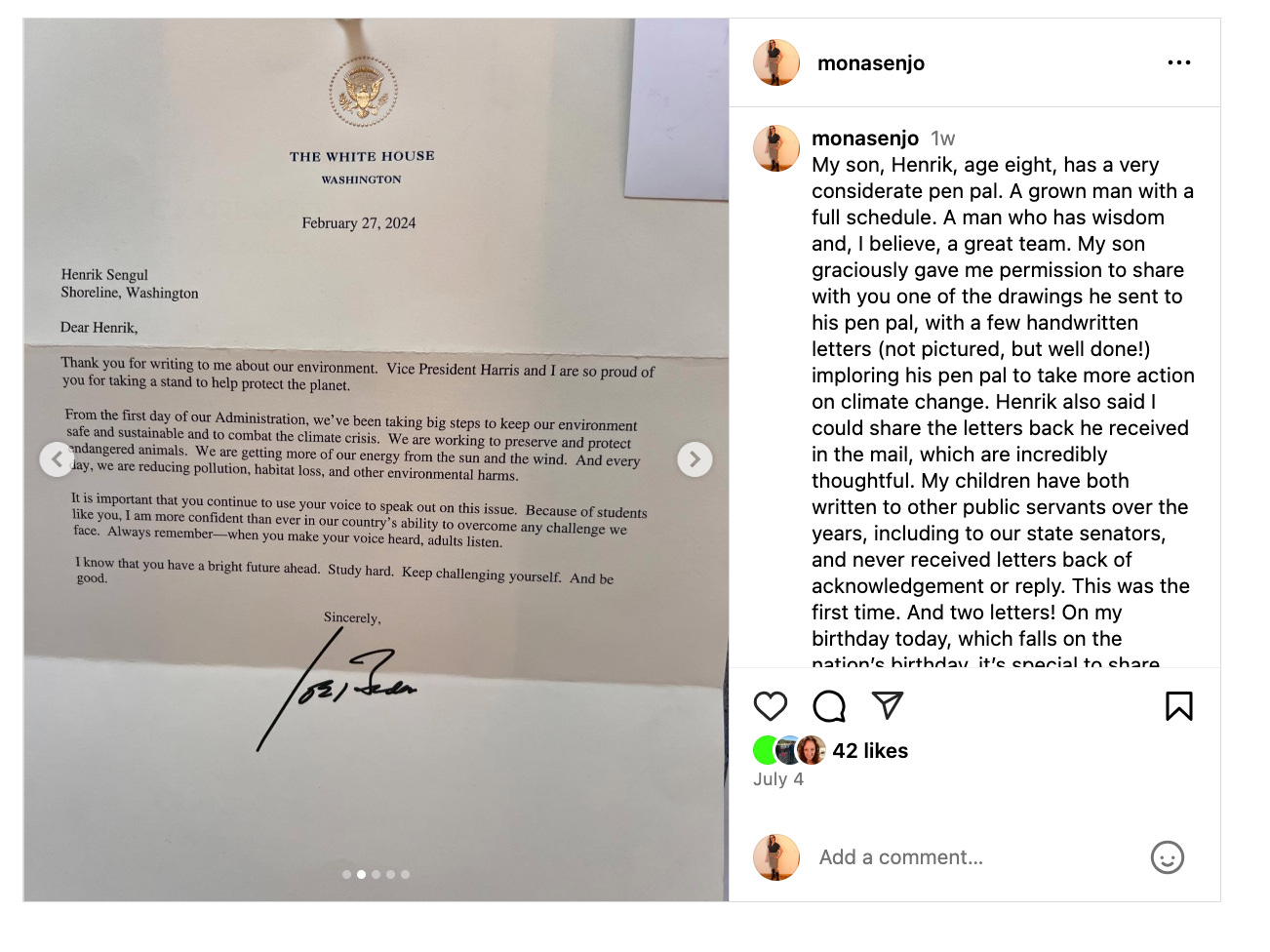

Unexpected connections. I shared in my socials that my eight-year-old son has a busy, considerate, grown man for a pen pal. His other pen pal is a sheep named Kendrick. See link for details.

Policy wonk. In my job, I am lucky to be hosted at the University of Washington’s Tech Policy Lab (TPL). Last Thursday, TPL founding co-director, Ryan Calo testified before the U.S. Senate about AI, stressing the need for a comprehensive federal law that protects Americans’ privacy and guidelines for businesses developing and implementing AI technologies. My favorite part was Calo’s reminder that people are “mediated through computer code.” 100%! “And a mediated consumer is a vulnerable one.” I’m hopeful policymakers will heed the recommendations. All of the speakers were powerful. Read the testimonies.

Roots. Summer, where the view never ages but always changes. My favorite time of year at home. Warm blues, long days, and salty air. I’ve been between San Juan Island, Shoreline, and, currently, I’m in Portland, Oregon as my partner finishes the Seattle to Portland bicycle (200+ mile) ride. Here’s a photograph of a special place, the end of San Juan Island looking southeast; I’m standing amid poppies.

Thanks for reading The Gift,

Monika

The Gift

Enjoy?

Forwarded this newsletter?

References

[1] Pryce, Amaya. 5 Simple Practices for a Lifetime of Joy (2015) Kathryn Pryce.

[2] ibid, 113

[3] Laakso, Joanna. (July 1, 2024) “AI and DYOR in etymology” https://kielioblog.wordpress.com/ai-and-dyor-in-etymology/

[4] Herzfeld, Noreen (Jan. 14, 2020) “A New Neighbor or a Divisive Force?,” Lecture. Fuller Missiology Studios. www.youtube.com/watch?v=wQRV5LWEtpg

[5] Arendt, Hannah. (1976 [1968]) The Origins of Totalitarianism. A Harvest Book. Hartcourt: New York. pg. 352

[6] Unexpected divergences and disruptions can certainly come from human-designed and human-centered AI. For instance, I wrote about investigative journalists using machine learning to hold corporations and governments accountable when I was reporting for the European Journalism Centre. I use Google Translate, Maps, Grammarly, and regularly feel misunderstood by my iPhone’s autocorrect.

[7] Pollack, Rachel. (2002) The Haindl Tarot. Red Wheel/Weiser. pg. 24-32

PS. Thank you for reading all the way to here. A book recommendation. Cloud Cuckoo Land by Anthony Doerr. Speculation, the joy of youth, care, and subtle plot twists that generate hope in readers, the book is a love song to the importance and long, precarious life of a story.