To almost be finished

How can you unmix milk from coffee? An essay about duration and mothering

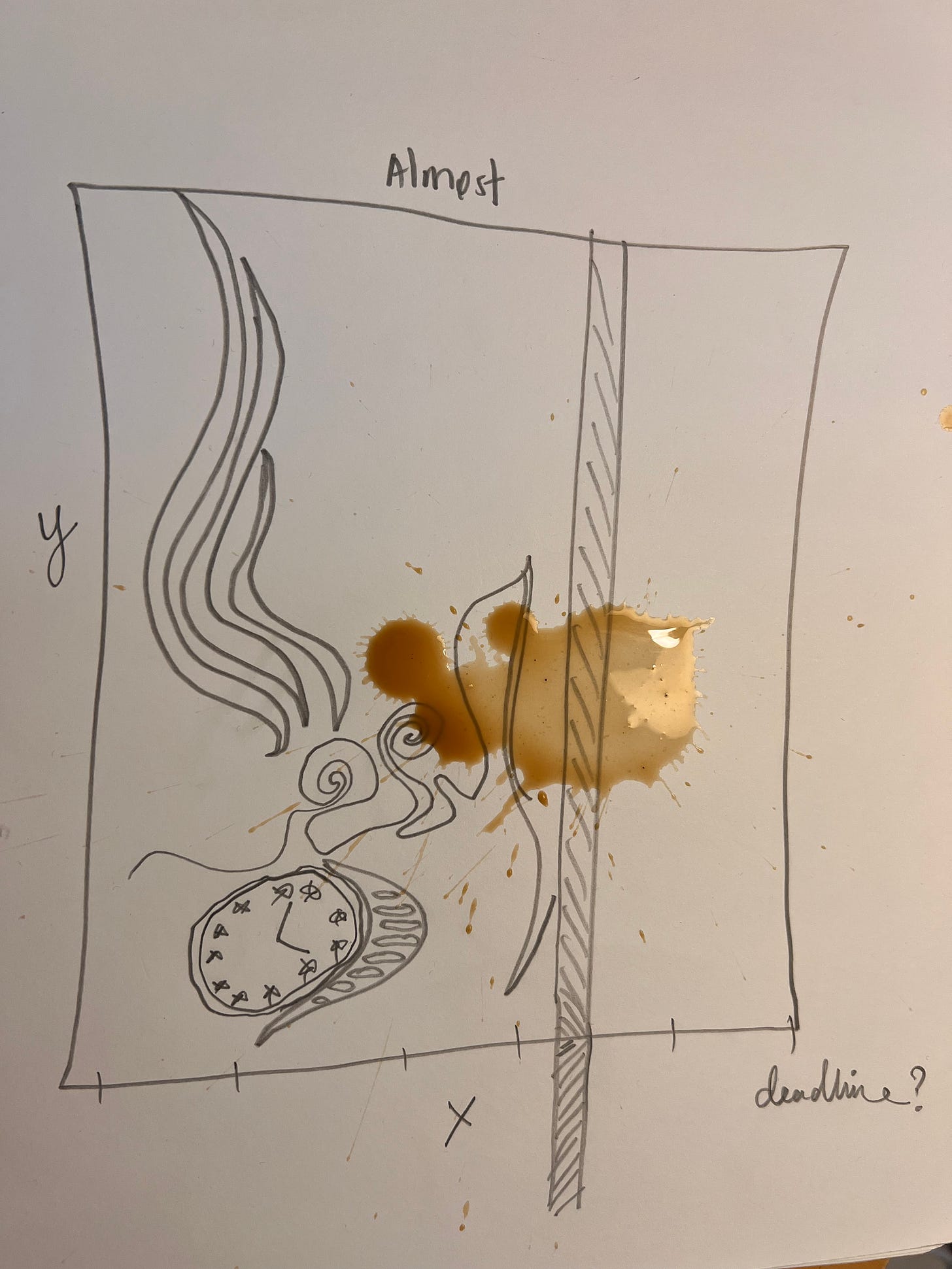

It's nearly there, I’m almost done. Not quite, but nearly. I can see where I want to be and I feel frustrated that I haven't arrived yet. Once, impatient by the throes of almost-thereness, I made a picture of the feeling. It's difficult to draw almost. Almost is very nearly, but not. I couldn't do something representational, like a smear of half-finished sentences, so I sketched a line graph. The x axis for time. The y for creation. I started the line low, it soared, digressed, swirled, and was interrupted by a thick chasm. The poor line stalled at probably about c3, in a grid. It could disappear. Chaos is near.

In the past, when I've made it through this chaotic space, I've done so only by retracing the flow so many times the lead bleeds into me and I become the paper. In other words, only when I've subsumed myself to the work does the chasm disappear and creation happens. In retrospect, it's hard to replicate, for every moment is different.

—

Recently, I've been trying to write something on AI writers. I want to say something about time, tools, and thinking. I motioned to AI writers, briefly, in the last edition of this newsletter, on the dullness of output by the likes of ChatGPT. When I say AI writers are boring and their output is dulling, it's not to minimize the leaps they have come or pretend that I could, or want, to design a better version. I am as amazed as the rest of us to observe an essay unfold on my screen in reply to a prompt. "Write an essay about the role of feminine desire in relation to death in Tolstoy's Anna Karenina.” Click. Ta-da. Gasp.

Perhaps, in time, I'll use the tool like I use a search engine. It's my extension, not me, but I hardly think about it, so convenient it is, and intuitive. When I remember, I give a nod of distain for the corporate overlords who control the doors to our information access and my intuitiveness. Search is useful for lateral reading or association work which are functions the engines themselves do not offer, that is thinking I must do.

But anyway, generative AI writers have gotten faster and the user interface is so seductively intuitive. It's only a matter of time before we have widespread normalization. And I must say something about this. About the second person. About time, consciousness, and higher thinking. But my point hasn't arrived yet. I need time to sit with it. And I feel snappy and impatient when I'm waiting.

—

I read about time and consciousness at the pool this week. A few days before my daughter's tenth birthday, which was yesterday, I checked out a collection of interdisciplinary conversations from the library and tucked it into the pool bag. Faded towels, extra swim shirts, goggles, sunscreen, pretzel chips, water bottles, ballpoint pens, sheets of paper, a rubber ball, changes of clothes, sweatshirts, a Rubik's cube, and “Great Minds Don't Think Alike: Debates on Consciousness, Reality, Intelligence, Faith, Time, AI, Immortality, and the Human” edited by Marcelo Gleiser. After I play a round of Marco Polo, just forty minutes of the family swim time remaining, I sit in the shade and look at the table of contents.

Before I can read a title, Henrik joins me. “What are you reading?” “I want to read about time,” I reply. Then I ask: “What do you imagine when you think of time?” He drips wet drops onto my bare legs and bites into a fist of pretzels. “The black-and-white clock on our wall,” he says, matter-of-factly. And don't we all? Time feels so matter-of-fact. Black and white. You have it or you don’t. I mean, I'm always running out, running up, or watching it fly by. I'm out of sync with the emotionless clock, which makes me impatient and snappy. How does that work? But I can't ask Henrik, he's already back in the pool.

Twenty-five minutes left of open swim. I started to wear an analog watch a decade ago when I was breastfeeding my newborn. She was early and slightly underweight. Nervous, we logged her feeding times, row by row, in a small notebook. Would the rows grow her up? I often cried when I nursed. It was painful, we were tired. I was in love and overwhelmed by her dependence. I think about this on the decade anniversary of her birth. Yesterday. I think about time and those long early days. What does an infant need? When do I give it? I tried to pencil it down, to learn from the data of my bodywork. She felt like a part of my body (she had been, for three seasons). I couldn't really think. So I made milk. I dozed. I held the baby. I cried. I gazed at her. I logged the time.

“Try not to rely on the clock,” Rose, the lactation consultant, cautioned. “You can, but relax. Feel. Imagine rivers of milk. Look at your baby, learn her expressions, you'll learn to sense when she's hungry.” In the anemic light of the hospital lactation conference room, Rose told stories to the weary-eyed new mothers. I remember one about her mother, she was a scientist.

“My mother meticulously measured an eight-ounce glass of beer, daily, for healthy nursing.” Rose never said, ‘Pour yourself a beer and relax, new mothers, let your milk come.’ But I did go home and pour myself a small glass. I relaxed. And at one point in those early weeks, I opened a book I'd gotten earlier in the year when I'd begun reading about time and time-keeping technologies. The historian of science Jimena Canales's A Tenth of A Second: A History.

Fifteen minutes left of open swim. Squinting in the sun, I look at the names inside “Great Minds Don't Think Alike,” intrigued by Chapter 5, “The Mystery of Time,” an interview between Jimena Canales and Paul Davies. Jimena Canales. I know her work! But I can't remember the point of her book. The tenth of a second. I want to look her up on the internet, but it’s a bad connection at the pool.

Later, I find her book. It's about thinking and time. The history of the quantification of a passing thought. A debate between Albert Einstein and Henri Bergson about thinking. How much time passes when we think a thought? Do we need to know? People decided we needed to know that. Measuring a tenth of a second satisfied this need and led to new thinking about thinking.

When I see the cover with Eadweard Muybridge's images of a galloping horse, stills of motion that accelerated daily life, I only remember that I was subject to the rule of a baby. Her rhythms didn't know standardized time. To synchronize with my baby, I divorced myself from the clock, temporarily, to keep my sanity. I was insane to everybody else. I slept at odd hours. I lost my train of thought. I divided. I gushed. And when I returned to work, I was contaminated, my thinking patterns bore stretch marks.

How much time does it take to think about a book? A decade, apparently.

—

Ten minutes until the end of open swim. Paul Davies says time does not move. It's just there. Rather, we move. He tells a relatable story about how we might confuse these concepts. “If you stand up and twirl around like this, you get an overwhelming sense that the universe is rotating. It's not rotating. I can see it's not rotating. But it feels like it is spinning round. In the same way, it feels like time is surging forward. But when I stop and think about it, it can't be. It's myself that is changing” he says (p. 131).

Time does not pass us, the flowing is an illusion, he claims, which we know from Albert Einstein (p. 132). Strangely, the laws of physics are symmetrical, but there are some breaking of these symmetries in our lives. “[There is] the fact that when you stir your cream in your coffee, it mixes up and [if] you keep stirring, it doesn't unmix” (p. 136).

I am eager to know Canales’s reply to this absurd situation. Even if you feel like the world is spinning, it's actually you. The coffee doesn't unmix with the cream, even if you mix hard. What does this mean?

—

The lifeguard blows her whistle. The time is over. Towels, showers, and wring out your bathing suit. Find your shoes. Be careful you don't drop your underwear in the puddle. Oops, it's okay. It will dry. Have a snack, eat at the table at the playground. Play as long as you like, but reapply sunscreen, please. I will return to the books later. I will write this essay on time and thinking later. I will take time off to celebrate the tenth birthday. I will write my newsletter later. More swimming. More snacks. Even, Barbie. Barbie! Ken is just Ken. What happens next? I go to sleep.

—

“When you say we are changing and it's not time, what is changing you? Are you saying there's a hidden something else behind it?” Canales asks Davies. Davies answers that selves are just the sum of our experiences. What of French philosopher Henri Bergson's theories of time as heterogeneous? I feel disappointed when the editorial format of the book appears to underscore Canales’s observation that “the subjective way we feel or experience time is now just a register for filmmakers and novelists” (p. 137). Subjective is just you.

“Nobody would think to go to an artist or poet to find the truth about time,” she says.

And, of course, she's right, in a way. While there's no dearth of scholarship that has continued in a Bergsonian tradition, it’s an effort to read. We’re ruled by one kind of time. Just ask my friend and colleague Louise Hickman, who lives in crip-time, to share the truth about time and thinking; or ask people who mother.

—

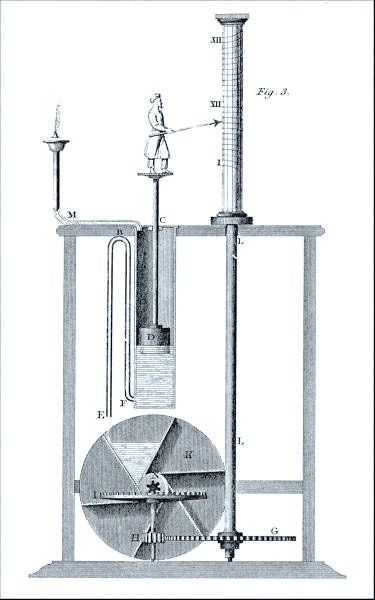

A year before I had a baby, I wrote a conference paper and poster about the "cultural practices” of data-driven writing work and technologies of timekeeping. It was an ambitious paper that began with a description of water clocks used in the medieval Islamic world, and before. These clocks were used to keep calculations in harmony with light time. Let’s say the sun always rises at six and sets at six. During short winter days, a minute is quite short. During long summer days, a minute is long. Because the sun always rises at six and sets at six. The precise length of a minute changes depending on the light length during the day. I wonder what people who lived in light time would think of our contemporary time-keeping habits? Aren't we tyrannical to insist that a minute is the same length in the summer and winter?

In my paper, I wrote that innovation in timekeeping can be read as an outcome of the way people already are living time in relation to their surroundings. We are doing the same, I suggested, in how we keep time now. We value data-driven global connections, so we find ways to track clicks. Ta-da. Gasp.

—

Home now, dinner made, kitchen mopped, swim suits drying. It's getting late, the waning moon is rising. I haven't finished my essay on AI and consciousness and time. I want to ask Caneles if she has a last word on time and heterogeneity, but I've lost her book, and left the library book somewhere else. When it’s time for bed, I tuck in the children and tell them about the spinning story and what happens to perception “Do you believe it?” I ask. “We already know about that,” they say. “We've done that before.” I’m sure they will do it again. Spinning and spinning until they fall over in a fit of giggles.

In the morning, I remember that Canales wrote about Bergson, “time was about the bursting forth of novelty into the scene of life” (133). The present. I decide I am still not finished, but I realized how I can unmix milk from coffee.

When the coffee is finished brewing, I will pour a cup, stir, and I don't add anything else.

Book recommendation

Homegoing

by Yaa Gyasi

In a conversation about Kitty Karr, which focused on reparations and passing (which I recommended a few weeks ago), I remembered Homegoing and highly recommend.

You might like it for

The book covers centuries and places—including Ghana, U.S., plantations, Harlem, and California

Parabolic stories of two sisters; intergenerational love and heartbreak

Gorgeous prose

“Yaw looked at her surprised, but she simply smiled. ‘When someone does wrong, whether it is you or me, whether it is mother or father, whether it is the Gold Coast man or the white man, it is like a fisherman casting a net into the water. He keeps only the one or two fish that he needs to feed himself and puts the rest in the water, thinking that their lives will go back to normal. No one forgets they were once captive, even if they are now free. But still, Yaw, you have to let yourself be free.’”

- Yaa Gyasi, p. 242

Until next time,

Monika

The Gift

Works cited

Canales, Jimena. 2009. A Tenth of a Second: A History. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Gleiser, Marcelo. 2021. Great Minds Don’t Think Alike. New York: Columbia University Press.

Gyasi, Yaa. 2017. Homegoing. First Vintage books edition. New York, NY: Vintage Books.